Introduction

The newly enacted Cannabis License Act, 2018 sets the Alcohol and Gaming Commission of Ontario (AGCO) as the regulator of cannabis retail outlets. For municipalities that have not opted out of having private cannabis retail outlets in their communities by January 22, 2019, the licensing and location of outlets will be determined by the AGCO with consideration given to comments provided by municipalities.1

Regulating the availability of cannabis is important in order to reduce the negative impacts of cannabis use in Wellington County, Dufferin County and the City of Guelph.2 Research regarding alcohol and tobacco has shown that increased availability of a substance results in increased consumption, which can lead to significant health and social harms and costs.3,4 While accessibility of legal cannabis is important for addressing the illegal market, this needs to be balanced with an evidence-informed approach that protects public health and safety.

A Public Health perspective on cannabis retail outlet options

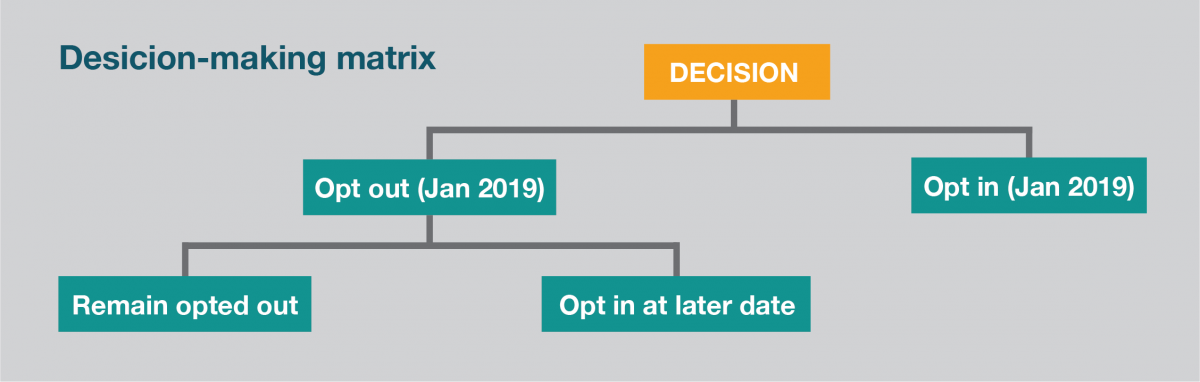

Municipalities have the authority to opt-out of cannabis retail stores by January 22nd, 2019. To opt-out, municipal councils must provide a notice of resolution to the AGCO.1

The decision to opt-out can be reversed, but any decision to opt-in is final.1

Considerations regarding each of these potential decisions are presented below:

- Opt-out by the January 22nd deadline and re-consider once more information is available:

Municipalities that choose to initially opt-out can monitor the situation and choose to opt-in later.

Ontario’s regulations for cannabis retail stores provide minimal restrictions on cannabis store locations, and do not provide any assurance to municipalities that they will have any control over the placement or number of retail outlets.

Opting out would disqualify a municipality from receiving a share of the two years of funding available from the province to support municipalities with cannabis retail. However, the economic gain from those funds should not be considered in isolation of the social and health costs that communities may incur due to increased access to cannabis retail (e.g. policing costs, by-law enforcement costs, emergency response costs, etc.).

The impact of cannabis legalization and its various retail models on community health and safety is not yet known. Opting out will allow municipalities to make a decision about cannabis retail after knowing more about the impacts of Ontario’s private retail model on communities that choose to opt-in across Ontario.

- Opt-in:

Municipalities that opt-in to cannabis retail stores will be unable to opt-out later if they are dissatisfied with cannabis retail in their communities.

If the municipality chooses to opt-in, Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph Public Health would encourage the municipality to advocate to the AGCO for the following considerations for store placement and hours in their community, where opportunities for input exist. This would likely have to be done on a license by license basis, which could become onerous depending on the number of cannabis store applications submitted in that municipality. (It should be noted that currently there are no provincial policies that assure that municipalities would have input into determining the locations or numbers of retail stores in their communities.)

|

ISSUE |

CONSIDERATION |

|

High retail outlet density can contribute to increased consumption and harms.5,6,7,8 |

Reduce cannabis retail outlet density through minimum distance requirements between cannabis retail outlets and limits on the overall number of outlets.9 Example: The City of Calgary has enacted a 300m separation distance between cannabis stores.10 |

|

Retail outlet proximity to youth-serving facilities can normalize and increase substance use.3,11,12 |

Prevent the role-modeling of cannabis use and reduce youth access through minimum distance requirements from youth-serving facilities such as schools, child care centres, and community centres.1,12 Example: The State of Washington has enacted a 1000ft (300m) separation distance requirement between cannabis retail stores and youth-serving facilities.13 |

|

Combined use of cannabis and other substances increases the risk of harms such as impaired driving.1 |

Discourage combined use of cannabis and other substances by prohibiting co-location and enacting minimum distance requirements between cannabis and alcohol or tobacco retail outlets.1,9 Example: KFL&A Public Health recommend a 200m separation distance between cannabis retail outlets and alcohol or tobacco retail outlets.14 |

|

Retail outlet proximity to other sensitive areas may negatively influence vulnerable residents.8,9 |

Protect vulnerable residents by limiting the clustering of cannabis retail outlets in low socioeconomic neighborhoods and enacting minimum distance requirements from other sensitive areas.4,9 Example: The City of Vancouver has restricted medical cannabis retail outlets to commercial zones instead of residential ones.15 |

|

Longer retail hours of sale significantly increases consumption and related harms.5,16 |

Reduce cannabis consumption and harms by limiting late night and early morning retail hours.5,16 Example: The Centre for Addiction and Mental Health recommends that cannabis retail hours reflect those established by the LCBO.16 |

Adapted with the permission of The Regional Municipality of Halton17

WDG Public Health’s Recommendation to Municipalities

Figure 1: Decision-making matrix

Rationale for a Public Health Approach to Cannabis Retail

Like alcohol and tobacco, cannabis can cause harm:

Cannabis use can affect learning and memory, lead to addiction, mental health problems, respiratory issues, and cause harm if used during pregnancy. Impairment from cannabis can also lead to injuries and fatalities, such as motor vehicle accidents.18,19

Increasing access to a substance can increase consumption and harm:

Research shows that increasing availability of a substance increases consumption and related harms (see Table 1). Increasing availability of a substance can make it more socially acceptable to use and can make people think it’s less harmful to use. Increasing availability makes it easier for a person to obtain a substance by reducing its total cost (e.g. time and travel) to obtain. This can increase impulse purchases by experimental users, occasional users, and users who are trying to quit.20 When a substance is easier to obtain, people are more likely to use it more. It can be expected that an increase in cannabis use would result in increased social and health harms. For example, increased alcohol availability is associated with higher levels of violence, assault, public disturbances, alcohol-related motor vehicle collisions and fatalities.5

Other jurisdictions that have legalized cannabis have seen a proliferation of retail stores

American jurisdictions that have legalized cannabis have expressed concern with the density of retail sales outlets and the close proximity of some outlets to schools, particularly in Denver, Colorado.21 Colorado legalized non-medical cannabis in 2012 and began licensing retail outlets in 2014.22 As of

June 2017, there were 491 retail cannabis stores in the state of Colorado, which exceeded the number of Starbucks (392) and McDonald’s (208). 65% of local jurisdictions in Colorado have banned medical and recreational cannabis businesses.22

Provincial regulations for cannabis retail stores provide limited municipal power and public health protection:

The newly released Ontario Regulations made under the Cannabis License Act, 2018, have set out requirements regarding retail store licensing and operations.23 The regulations establish a minimum distance of 150 metres between cannabis retail stores and schools, and have set the store hours of operation between 9:00am to 11:00pm.

These regulations do not contain required separation distances from other sensitive areas (such as recreation centres, universities, addiction treatment facilities, hospitals, etc.), and no required separation distances from other cannabis stores. Municipalities were also not granted the power to create their own by-laws to control density and separation distances. This may lead to a clustering of cannabis stores in certain neighborhoods. Research from alcohol, tobacco, and cannabis has shown that lower-income neighborhoods tend to have a higher density of outlets.3,24,25,26

It is still unknown how much influence municipalities will have over AGCO decisions on store locations and density.1

Balance is needed when considering access to legal cannabis:

Ensuring access to a regulated and legal supply of cannabis is important, especially since the latest Canadian data indicates that 15% of Canadians have used cannabis in the past year.27

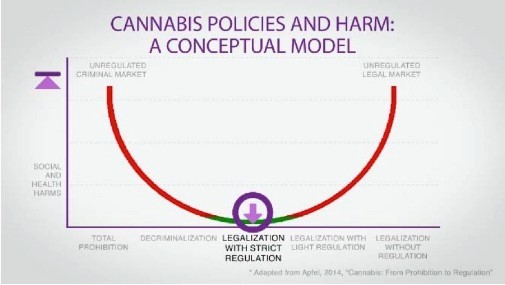

A public health approach to cannabis legalization strives to minimize the health and social harms from substances and recognizes that the greatest harms occur at the extremes of prohibition and commercialization for profit (Figure 2). Legalization without strict regulations, such as restrictions on retail density and locations, may increase cannabis-related harms.2

While it is important to provide sufficient access to a regulated legal supply of cannabis to avoid the risks of an illicit market, too much access may increase consumption and associated harms.

In April, communities across Ontario will continue to have access to a legal source of cannabis through the online Ontario Cannabis Store (although it should be noted that some vulnerable groups, such as those without an address or credit card, may have limited access). Since the impacts of different retail models across Canada are not yet known, it is important to consider a precautionary approach with stricter regulations to try and minimize health and social problems.2

Financial opportunities should be considered with potential health and social costs in mind:

Municipal governments that permit cannabis retail stores will receive a population-based share of $40 million in funding from the province for two years, and potentially additional funding from taxes.1 Cannabis retail stores would also create local business opportunities, however municipalities would not be permitted to license cannabis retail stores.

These financial and economic gains should be considered in light of the potential social and health costs to the community.

In 2014, before legalization, cannabis was already the fourth most costly substance in Canada in terms of social and health impacts. Costs associated with cannabis include: healthcare, lost productivity, criminal justice and other direct costs to society, totaling at least $2.8 billion.28

Early findings from legalization in Colorado and Washington states have shown increases in cannabis use among young adults and adults, cannabis-related emergency department visits and hospitalizations, and cannabis-related motor vehicle collision fatalities.29

Municipalities may also incur increased costs to support police and by-law enforcement to protect areas where smoking is not permitted and to respond to nuisance complaints. While the impact of retail stores on these outcomes has not yet been established, research supports the finding that increased availability of a substance is generally associated with increased consumption and harms.

Figure 2: Reproduced with permission from Centre for Addiction and Mental Health: Cannabis Policy Framework. Adapted from Alice Rap: Cannabis – From Prohibition to Regulation.30

Conclusion

Increased access to substances, increases consumption and related harms. Ontario’s regulations for cannabis retail stores provide minimal restrictions on cannabis store locations, and minimal power for municipalities to set their own regulations. It is not yet known how much influence municipalities will be have over AGCO decisions on store locations and density. Since the decision to opt-in is final, and the impact of Ontario’s private retail model on communities is not yet known, WDGPH recommends monitoring the impacts in other communities before choosing to opt in.

References

- Association of Municipalities of Ontario. Briefing: Municipal governments in the Ontario recreational cannabis framework [Internet]. 2018 Oct [cited 2018 Nov 3]. Available from: http:// www.amo.on.ca/AMO-PDFs/Reports/2018/Briefing-Municipal-Governments-in-the-Ontario-Recr. aspx

- Government of Canada. A Framework for the Legalization and Regulation of Cannabis in Canada. The final report of the task force on cannabis legalization and regulation [Internet]. 2016 Nov [cited 2018 Nov 3]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs- medication/cannabis/laws-regulations/task-force-cannabis-legalization-regulation/framework- legalization-regulation-cannabis-in-canada.html

- Babor T, Caetano R, Cassell S, Edwards G, Giesbrecht N, Graham K. Alcohol no ordinary commodity: Research and public policy (Second ed.). New York, USA: Oxford University Press; 2010.

- Smoke-Free Ontario Scientific Advisory Committee, Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion. Evidence to Guide Action: Comprehensive Tobacco Control in Ontario (2016) [Internet]. 2017 Apr [cited 2018 Nov 3]. Available from: https://www.publichealthontario.ca/en/ eRepository/SFOSAC%202016_FullReport.pdf

- Popova S, Giesbrecht N, Bekmuradov D, Patra J. Hours and days of sale and density of alcohol outlets: Impacts on alcohol consumption and damage: A systematic review. Alcohol and Alcoholism [Internet]. 2009 [cited 2018 Nov 3]; 44 (5): 500-516. Available from: https://academic. oup.com/alcalc/article/44/5/500/182556

- World Health Organization. Global strategy to reduce the harmful use of alcohol [Internet]. 2010 [cited 2018 Nov 3]. Available from: http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/msbalcstragegy.pdf

- Borodovsky JT, Lee DC, Crosier BS, Gabrielli JL, Sargent JD, Budney AJ. US cannabis legalization and use of vaping and edible products among youth. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017; 177:299-306. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28662974

- Mair C, Freisthler B, Ponicki WR, Gaidus A. The impacts of marijuana dispensary density and neighborhood ecology on marijuana abuse and dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015; 154: 111-116. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26154479

- Alberta Health Services. AHS Recommendations on cannabis regulations for Alberta municipalities [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2018 Nov 3]. Available from: https://rmalberta.com/wp- content/uploads/2018/05/Webinar-recording-Cannabis-and-Public-Health-AHS-Cannabis- Information-Package-for-Municipalities.pdf

- City of Calgary. Cannabis store business guide [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2018 Nov 3]. Available from: http://www.calgary.ca/PDA/pd/Pages/Business-licenses/Cannabis-Store.aspx

- 11. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of the Surgeon General. Facing addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s report on alcohol, drugs, and health [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2018 Nov 3]. Available from: http://www.williamwhitepapers.com/pr/dlm_uploads/2016- Surgeon-Generals-Report-Facing-Addiction-in-America.pdf

- Canadian Pediatric Society. Position Statement: Cannabis and Canada’s children and youth [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2018 Nov 3]. Available from: https://www.cps.ca/en/documents/position/ cannabis-children-and-youth

- Washington State Liquor and Cannabis Board. Distance from restricted entities [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2018 Nov 3]. Available from: https://lcb.wa.gov/mjlicense/distance_from_restricted_entities

- Kingston, Frontenac and Lennox & Addington Public Health. Memorandum: Provincial recommendations on the cannabis retail system; 2018.

- City of Vancouver. Regulations for medical-marijuana related businesses [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2018 Nov 3]. Available from: https://vancouver.ca/doing-business/cannabis-related-business- regulations.aspx

- Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. Submission to the Ministry of the Attorney General and the Ministry of Finance: Cannabis regulation in Ontario [Internet]. 2018 Sept [cited 2018 Nov 3]. Available from: https://www.camh.ca/-/media/files/pdfs-–public-policy-submissions/camhsubmission-cannabisretail_2018-09-25-pdf. pdf?la=en&hash=1237D4AF4316606BC546D8C6D1D1EF1D84C7C00B

- The Regional Municipality of Halton. Cannabis retail outlet considerations for municipalities; 2018.

- Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. Clearing the Smoke on Cannabis Highlights [Internet]. 2016 Sept [cited 2018 Nov 3]. Available from: http://www.ccdus.ca/Resource%20Library/CCSA- Clearing-the-Smoke-on-Cannabis-Highlights-2016-en.pdf

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids. The current state of evidence and recommendations for research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2017. Available from: https://www.nap.edu/catalog/24625/ the-health-effects-of-cannabis-and-cannabinoids-the-current-state

- Ontario Public Health Association. Position Paper: The public health implications of the legalization of recreational cannabis [Internet]. [cited 2018 Nov 3]. Available from: http:// www.opha.on.ca/getmedia/6b05a6bc-bac2-4c92-af18-62b91a003b1b/The-Public-Health- Implications-of-the-Legalization-of-Recreational-Cannabis.pdf.aspx?ext=.pdf

- Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. Cannabis regulation: Lessons learned in Colorado and Washington State [Internet]. 2015 Nov [cited 2018 Nov 3]. Available from: http://www.ccdus.ca/ Resource%20Library/CCSA-Cannabis-Regulation-Lessons-Learned-Report-2015-en.pdf

- Rocky Mountain High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area. The legalization of marijuana in Colorado: The Impact Volume 5 [Internet]. 2018 Sept [cited 2018 Nov 3]. Available from: https://rmhidta.org/ files/D2DF/FINAL-%20Volume%205%20UPDATE%202018.pdf

- Ministry of the Attorney General. News Release: Ontario Establishes Strict Regulations for the Licensing and Operation of Private Cannabis Stores [Internet]. 2018 Nov [cited 2018 Nov 20]. Available from: https://news.ontario.ca/mag/en/2018/11/ontario-establishes-strict-regulations-for-the-licensing-and-operation-of-private-cannabis-stores.html

- Bluthenthal RN, Cohen DA, Farley TA, Scribner R, Beighley C, Schonlau M, et al. Alcohol availability and neighborhood characteristics in Los Angeles, California and Southern Louisiana. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine [Internet]. 2008 [cited 2018 Nov 20]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2430119/pdf/11524_2008_Article_9255.pdf

- Jones-Webb R, Karriker-Jaffe KJ. Neighborhood disadvantage, high alcohol content beverage consumption, drinking norms, and drinking consequences: A mediation analysis. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2018 Nov 20]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3732692/pdf/11524_2013_Article_9786.pdf

- Shi Y, Meseck K, Jankowska MM. Availability of Medical and Recreational Marijuana stores and neighborhood characteristics in Colorado. Journal of Addiction [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2018 Nov 20]. Available from: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/jad/2016/7193740/

- Government of Canada. Canadian Tobacco, Alcohol, and Drugs Survey (CTADS): Summary of results for 2017 [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2018 Nov 3]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/ health-canada/services/canadian-tobacco-alcohol-drugs-survey/2017-summary.html

- Canadian Substance Use Cost and Harms Scientific Working Group. Report in Short: Canadian Substance Use Cost and Harms 2007-2014 [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2018 Nov 3]. Available from: http://csuch-cemusc.ccsa.ca/Resource%20Library/CSUCH-Canadian-Substance-Use-Costs- Harms-Report-in-short-2018-en.pdf

- Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph Board of Health. BOH report – BH.01.SEP0518.R26 Cannabis Legalization Update [Internet]. 2018 Sept 5 [cited 2018 Nov 3]. Available from: https://www. wdgpublichealth.ca/sept-2018-boh-cannabis-legalization-update-report

- Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH). Cannabis Policy Framework. [Internet]. 2014. [cited 2018-Nov-03]. Available from: https://www.camh.ca/-/ media/files/pdfs—public-policy-submissions/camhcannabispolicyframework-pdf. pdf?la=en&hash=25B173918327AA9FE4A11A5286B0B79495CE2797