Report to: Board of Health

Meeting Date: March 2, 2016

Report Number: BOH Report – BH.01.MAR0216.R04

Prepared by: Sam Stevenson, Health Promotion Specialist; Amy Estill, Health Promotion Specialist; Jennifer McCorriston, Manager, Chronic Disease, Injury Prevention & Substance Misuse; Liz Robson, Manager, Reproductive Health

Approved by: Rita Sethi, Director, Community Health & Wellness

Submitted by: Dr. Nicola Mercer, Medical Officer of Health & CEO

Recommendation(s)

(a) That the Board of Health receives this report for information.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

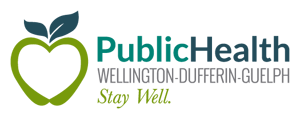

Infographic Summary

Alcohol Harm Prevention Strategy

The Issue

- Second leading preventable risk for disability, next to tobacco

- 463 local hospital visits per year because of alcohol

- Four people per year killed in a traffic accident involving alcohol in WDG

- 13 poeple per year severely injured in a traffic accident involving alcohol in WDG

- Low local awareness and concern about alcohol desease risks

- Substantial local support for improved harm prevention policy

The Strategy:

- Build healthy public policy: help improve municipalities alcohol risk management policies

- Create supportive environments: raise public awareness of alcohol’s harms

- Develop personal skills: support school and family based prevention activities

- Strengthen community action: plan alcohol harm prevention projects with local health, enforcement and service groups

- Reorient health services: lead a preconception health screening study with primary care providers

BACKGROUND

Alcohol is the second leading preventable risk factor for disability in Canada.1 Consumption of alcohol, especially at high-risk levels, is associated with over 60 diseases, including cancer, cardiovascular disease, digestive diseases, and neuropsychiatric conditions.2 Much of the disease burden of alcohol is related to unintentional and intentional injury, including traffic fatalities, violence, and suicide.2 Moreover, maternal drinking during pregnancy can cause Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder, a range of disabilities that can have lasting effects on a child that is exposed to alcohol in utero.3 The estimated monetary social cost of alcohol in Canada in 2002 was approximately $14.6 billion dollars, just short of tobacco at $17 billion and about twice that of illegal drugs at $8.2 billion.4

In 2013, 81% of Wellington County, Dufferin County, and City of Guelph (WDG) residents aged 19 years and older reported drinking alcohol in the last 12 months and almost half reported exceeding at least one of Canada’s Low-Risk Alcohol Drinking Guidelines (LRADGs).5 In both of those cases, local drinking rates were significantly higher than the Ontario rates which were 72% and 41%, respectively.5 Among local women of childbearing age (15-44 years old), 62% reported exceeding Canada’s LRADGs.5 This is especially concerning given the fact that approximately half of pregnancies are unplanned; a women may expose a fetus to alcohol without even realizing that she is pregnant.6 In 2012, about half of grade 10 students reported heavy drinking (consuming 5 or more drinks on one occasion) at least once per year and one in three University of Guelph students were classified as heavy, frequent drinkers.5

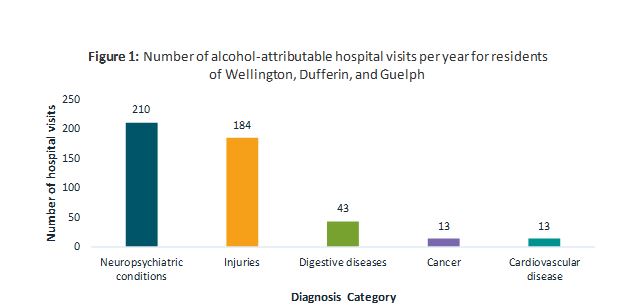

Locally, alcohol is a significant cause of chronic disease and injury. Data from 2011 to 2013 estimates that alcohol is directly responsible for an average 463 hospital visits per year for WDG residents7 (Figure 1). The total yearly cost of those hospital visits attributable to alcohol in WDG was conservatively estimated to be about $1.27 million, not including physician fees.7 Therefore, reducing alcohol consumption presents an opportunity for significant cost savings at the provincial and municipal level.

Figure 1 Data Table

| Diagnosis Category | Number of Hospital Visits |

|---|---|

| Neuropsychiatric conditions | 210 |

| Injuries | 184 |

| Digestive diseases | 43 |

| Cancer | 13 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 13 |

Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph Public Health’s (WDGPH’s) recent community opinions survey of over 600 WDG residents reveals a low level of knowledge that drinking alcohol increases a person’s risk of chronic disease.8 Survey participants were asked three questions to test their knowledge of alcohol’s relationship to chronic diseases. Only 5% of the survey participants correctly answered all three questions about alcohol’s link to chronic disease, and 27% answered none of the questions correctly.8 Despite the fact that even one drink per day increases a person’s risk of developing cancer, 50% of participants who drank daily reported being not concerned at all about their cancer risk due to drinking.8,9 These findings illustrate the need to educate WDG residents on the health harms associated with alcohol.

Furthermore, drinking and driving is still an issue in WDG. Local statistics from the Ministry of Transportation of Ontario show that from 2004 to 2013 there were 41 local fatalities and 126 major injuries related to drinking and driving.10 The community opinions survey confirms that drinking and driving was perceived by participants to be the number one alcohol-related issue in the area.7 Alcohol-related violence and over-serving in bars, pubs and restaurants were also perceived to be top alcohol-related issues in the community.8

Because healthy public policy plays an important role in reducing alcohol-related harm, the community opinions survey also explored residents’ level of support for potential municipal and provincial alcohol-related policies. According to the survey, the majority of participants supported the following policy options: banning the sale of energy drinks that are premixed with alcohol (71% agreement), requiring alcohol to be sold with a warning label (55% agreement), and pricing alcohol drinks based on alcohol content (51% agreement).8 Over half (56%) of residents also disagreed with allowing alcohol to be sold in convenience stores.8

ANALYSIS/RATIONALE

Harmful alcohol use, which includes overconsumption and consumption during pregnancy, is not simply an issue of personal choice. Socio-environmental factors such as culture, policy, and the built environment strongly influence an individual’s choice to drink. As such, WDGPH recently developed an evidence-based strategy to target socio-environmental factors at both the local and provincial level, while also addressing individual factors so that people can make better-informed alcohol-related decisions.

WDGPH ’s strategy includes the following local activities:

- offering municipalities a standardized assessment of their alcohol risk management policies and providing consultation for improvement;

- leading a Preconception Health Screening Pilot Project with Family Health Teams;

- assisting the University of Guelph in on- and off-campus alcohol harm prevention activities;

- supporting school-based alcohol harm prevention activities, which may include a youth engagement approach to build resiliency and refusal strategies;

- making screening, brief intervention, and referral services available on WDGPH’s website;

- raising awareness of Canada’s Low Risk Alcohol Drinking Guidelines and the harms of alcohol; and

- mobilizing community partners to plan, implement, and evaluate local alcohol harm prevention activities.

WDGPH’s alcohol strategy will also support provincial policy change through research, public education and advocacy. Although Ontario recently scored first among Canada’s provinces for its alcohol harm-prevention laws and programs (e.g. prohibiting sales to youth and marketing restrictions), room exists for improvement.11 For example, setting minimum prices for alcoholic beverages based on ethanol content[1] and slightly increasing all minimum prices will likely create a significant reduction in alcohol-related disease, injuries, and death.12,13,14,15,16 A recent modelling study for Ontario also suggests that increasing the minimum price of alcohol will create a minimal decrease in drinking prevalence among moderate drinkers (1.17%) but a higher decrease in drinking prevalence among hazardous (1.43%) and harmful drinkers (2.10%).14

WDGPH is pleased with the Ontario Government’s recent announcement that it will develop a comprehensive, province-wide policy to reduce alcohol-related harm.17 The policy will include four main pillars: promotion and prevention, social responsibility, harm reduction and treatment. Although this shows the province’s commitment to addressing alcohol related harms, making gains may be a difficult task given alcohol’s social and economic context. WDGPH looks forward to working with local health, law enforcement, and social service providers to plan and implement activities that meet the needs of many stakeholders. The vision is a community that is free from alcohol-related harm.

Ontario Public Health Standards

- Requirement 3 (under Chronic Disease Prevention): The board of health shall work with school boards and/or staff of elementary, secondary, and post-secondary educational settings, using a comprehensive health promotion approach, to influence the development and implementation of healthy policies, and the creation or enhancement of supportive environments to address the following topics: … alcohol use. (p. 28)

- Requirement 6 (under Chronic Disease Prevention): The board of health shall work with municipalities to support healthy public policies and the creation or enhancement of supportive environments in recreational settings and the built environment regarding the following topics: … alcohol use. (p. 29)

- Requirement 7 (under Chronic Disease Prevention): The board of health shall increase the capacity of community partners to coordinate and develop regional/local programs and services related to: … alcohol use. (p. 30)

- Requirement 11 (under Chronic Disease Prevention): The board of health shall increase public awareness in the following areas: … alcohol use. (p. 30)

- Requirement 12 (under Chronic Disease Prevention): The board of health shall provide advice and information to link people to community programs and services on the following topics: … alcohol use. (pp. 30-31)

- Requirement 2 (under Prevention of Injury and Substance Misuse): The board of health shall work with community partners, using a comprehensive health promotion approach, to influence the development and implementation of healthy policies and programs, and the creation or enhancement of safe and supportive environments that address the following: … alcohol. (pp. 33-34)

- Requirement 4 (under Prevention of Injury and Substance Misuse): The board of health shall increase public awareness of the prevention of injury and substance misuse in the following areas: … alcohol. (p. 34)

- Requirement 5 (under Prevention of Injury and Substance Misuse): The board of health shall use a comprehensive health promotion approach in collaboration with community partners, including enforcement agencies, to increase public awareness of and adoption of behaviours that are in accordance with current legislation related to the prevention of injury and substance misuse in the following areas: … alcohol. (pp. 34-35)

[1] If all alcoholic beverages are subject to minimum pricing of $1.60 per 17.05 millilitres of ethanol (a standard drink in Canada), the minimum retail price of a bottle containing 34.1 millilitres of ethanol (two standard drinks) would be $3.20.

WDGPH Strategic Commitment

| DIRECTION | APPLIES? (YES/NO) |

|---|---|

| Health Equity: We will provide programs and services that integrate health equity principles to reduce or eliminate health differences between population groups. | YES |

| Organizational Capacity: We will improve our capacity to effectively deliver public health programs and services. | NO |

| Service Centred Approach: We are committed to providing excellent service to anyone interacting with Public Health. | NO |

| Building Healthy Communities: We will work with communities to support the health and well-being of everyone. | YES |

Health Equity

Determinants of health, such as gender, age, income, education, living situation and racial background, were all considered in the development of the alcohol strategy. When examining alcohol consumption and risk, groups most likely to exceed the Low-Risk Alcohol Drinking Guidelines include males, young adults, urban-dwellers, Caucasians, people with post-secondary education, single individuals, and those with a higher income. Although overall alcohol consumption increases with income, local data suggests that individuals of lower income suffer more from the harms associated with alcohol. For example, the number of alcohol-related hospital visits per person is greater in areas with lower income levels compared to areas with higher income levels.7 One can speculate that access to care and social supports may contribute to this inequity in harms, however what truly accounts for this difference is unclear and emerging research will be monitored to build an understanding.

From a policy lens, it is important to examine the impact of potential policy options on various populations. For example, one area for provincial policy improvement is increasing the minimum price of alcoholic beverages. Increased prices are associated with decreased binge drinking.12 Canadian evidence also shows that periodic increases in minimum unit pricing are associated with reduced alcohol-attributable hospital visits and deaths wholly attributable to alcohol.13,14 While this policy is promising, how will an increase in minimum pricing affect health inequities?

Increasing the price of alcohol is considered the most promising policy to reduce inequities in alcohol-related harm.18 A recent modelling study in England found that with a minimum unit alcohol price set at a level similar to $1.60 CAD, harmful drinkers with the lowest income would experience a 7.6 fold greater decrease in standard units of alcohol consumed per year (300 units, or 3.0 litres) compared to harmful drinkers with the highest income.16 Furthermore, harmful drinkers with the lowest income would accrue just over 80% of the population-wide reductions in premature death due to the minimum unit pricing. This study suggests that increasing minimum unit pricing in WDG will reduce differences in harmful drinking and alcohol-related harm between people with low and high incomes. This is important because those with lower incomes in Canada generally have a greater risk of death from alcohol-use disorders, liver cirrhosis, cancer, and unintentional injuries than those with higher incomes.18

Throughout strategy planning and implementation, and as evidence emerges, activities under the strategy will be assessed for their potential to increase differences in alcohol-related harm because of people’s social conditions. Activities that will likely increase such differences in harm will be avoided.

Appendices

N/A

References

1. World Health Organization. Global health risks: Mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks [Internet]. 2009 [cited 2016 Jan 5]. Available from: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/GlobalHealthRisks_report_full.pdf

2. Rehm J, Patra J, Popova S. Alcohol‐attributable mortality and potential years of life lost in Canada 2001: implications for prevention and policy. Addiction. 2006 [cited 2015 Jan 10];101(3):373-84.

3. Granville, A. FASD provincial roundtable report. [Internet] Sept, 2015 [cited 2016 Feb 3]. Available from: http://www.children.gov.on.ca/htdocs/English/topics/specialneeds/fasd/index.aspx

4. Rehm J, Baliunas D, Brochu S, Fisher B, Gnam W, Patra J, et al. The costs of substance abuse in Canada in 2002 [Internet]. 2006 Mar [cited 2015 Jan 10]. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Svetlana_Popova4/publication/225091976_The_Costs_of_Substance_Abuse_in_Canada_2002/links/0912f50b9440f77f6c000000.pdf

5. Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph Public Health. A report on alcohol in Wellington, Dufferin, and Guelph [Internet]. 2015 Aug [cited 2016 Jan 10]. Guelph, ON: Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph Public Health. Available from: http://wdgpublichealth.ca/sites/default/files/wdgphfiles/Alcohol%20HSR%20-%20FINAL%20%28August%202015%29.pdf

6. Ontario Public Health Association. Shift- Enhancing the health of Ontarians: A call to action for preconception health and care [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2016 Feb 3]. Toronto, ON: Ontario Public Health Association. Available from: http://www.opha.on.ca/getmedia/2da52762-6614-40f7-97ff-f2a5043dea21/OPHA-Shift-Enhancing-the-health-of-Ontarians-A-call-to-action-for-preconception-health-promotion-and-care_1.pdf.aspx

7. Jeong, E. Rate, cost and geographical distribution of alcohol-attributable hospitalizations in a local public health jurisdiction in southwestern Ontario [unpublished master’s thesis]. [Guelph (ON)]: University of Guelph; 201

8. Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph Public Health. Community opinions on alcohol in Wellington, Dufferin, and Guelph: results from the 2014 Wellington, Dufferin, Guelph Alcohol Survey [Internet]. Guelph, ON: Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph Public Health; 2015 Sep [cited 2016 Jan 7]. Available from: http://wdgpublichealth.ca/sites/default/files/wdgphfiles/Alcohol%20Report%20-%20FINAL%2021_09_2015.pdf

9. Beirness D, Gliksman L, Paradis C, Stockwell T. Alcohol and health in Canada: a summary of evidence and guidelines for low-risk drinking [Internet]. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Centre on Sustance Abuse; 2011 Nov 25 [cited 2016 Jan 28]. Available from: http://www.ccsa.ca/Resource%20Library/2011-Summary-of-Evidence-and-Guidelines-for-Low-Risk%20Drinking-en.pdf

10. Personal communication with the Ministry of Transportation of Ontario, 2015 Sep 11.

11. Giesbrecht N, Wettlaufer A, April N, Asbridge M, Cukier S, Mann R, et al. Strategies to reduce alcohol-related harms and costs in Canada: a comparison of provincial policies [Internet]. Toronto, ON: Centre for Addiction & Mental Health; 2013 [cited 2016 Jan 28]. Available from: http://www.camh.ca/en/research/news_and_publications/reports_and_books/Documents/Strategies%20to%20Reduce%20Alcohol%20Related%20Harms%20and%20Costs%202013.pdf

12. Xuan Z, Chaloupka FJ, Blanchette JG, Nguyen TH, Heeren TC, Nelson TF, et al. The relationship between alcohol taxes and binge drinking: evaluating new tax measures incorporating multiple tax and beverage types. Addiction [Internet]. 2015 Mar 1 [cited 2015 Jan 10];110(3):441-50. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4441276/pdf/nihms691298.pdf

13. Stockwell T, Zhao J, Martin G, Macdonald S, Vallance K, et al. Minimum alcohol prices and outlet densities in British Columbia, Canada: estimated impacts on alcohol-attributable hospital admissions. Am J Public Health. 2013 Nov [cited 2015 Jan 10];103(11):2014-20.

14. Zhao J, Stockwell T, Martin G, Macdonald S, Vallance K, Treno A, et al. The relationship between minimum alcohol prices, outlet densities and alcohol‐attributable deaths in British Columbia, 2002–09. Addiction. 2013 Jun 1 [cited 2015 Jan 10];108(6):1059-69.

15. Hill-McManus D, Brennan A, Stockwell T, Giesbrecht N, Thomas G, Zhao J, et al. Model-based appraisal of alcohol minimum pricing in Ontario and British Columbia: a Canadian adaptation of the Sheffield Alcohol Policy Model Version 2. 2012 May 12 [cited 2015 Jan 10]. ScHARR: University of Sheffield. Available from: http://dspace.library.uvic.ca:8080/bitstream/handle/1828/4792/Alcohol%20Minimum%20Pricing%20Ontario%20BC%20December%202012.pdf?sequence=1